Monthly Archives: September 2016

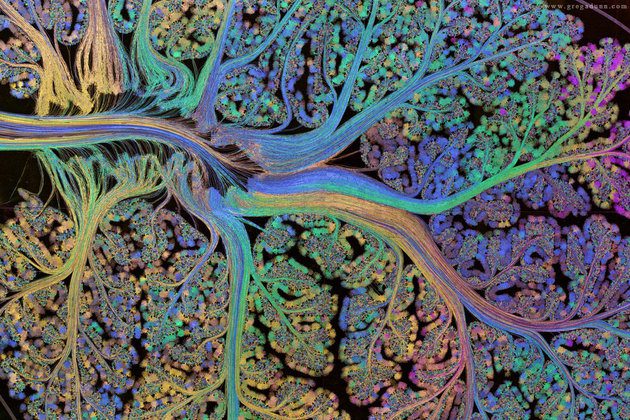

Balanced Inhibition-Excitation

Another idea that I consider ill-conceived is the notion that neural networks need to have balanced inhibition-excitation. This means that with every rise (or fall) of overall excitation of the network, inhibition has to closely match it.

On the one hand, this looks like a truism: excitation activates inhibitory neurons and therefore larger excitation means larger inhibition, which reduces excitation. However, the idea in the present form stems from neural modeling: conventional neural networks with their uniform neurons and dispersed connectivity easily either stop spiking because of a lack of activity, or spike at very high rates and ‘fill up’ the whole network to capacity. It is difficult to tune them to the space in-between, and difficult to keep them in this space. Therefore it was postulated that biological neural networks face the same problem and that here also excitation and inhibition need to be closely matched.

First of all inhibition is not simple. Inhibitory-inhibitory interactions make the simplistic explanation unrealistic, and the many different types of inhibitory neurons that have evolved again make it difficult to implement the balanced inhibition-excitation concept.

Secondly, more evolved and realistic neural networks do not face the tuning problem, they are resilient even with larger and smaller differences between inhibition and excitation.

Finally, there are a number of experimental findings showing that it is possible to tune inhibition in the absence of tuning excitation. In a coupled negative feedback model this simply means that the equilibrium values change. But some excitatory neurons may evolve strong activity without directly increasing their own inhibition. Inhibition needs not to be uniformly coupled to excitation, if a network can tolerate fairly large fluctuations in excitation.

Ubiquitous interneurons may still be responsible for guarding lower and upper levels of excitation (‘range-control’). This range may still be variably positioned.

In the next post I want to discuss an interesting form of regulation of inhibitory neurons, which also does not fit well with the concept of balanced inhibition-excitation.