Some time ago, I suggested that the theoretical view on balanced inhibition/excitation (in cortex and cortical models) is probably flawed. I suggested that we have a loose regulation instead, where inhibition and excitation can fluctuate independently.

The I/E balance stems from the idea that the single pyramidal neuron should receive approximately equal strength of inhibition and excitation, in spite of the fact that only 10-20% of neurons in cortex are inhibitory (Destexhe2003, more on that below). Experimental measurements have shown that this conjecture is approximately correct, i.e. inhibitory neurons make stronger contacts, or their influence is stronger relative to excitatory inputs.

The E-I balance in terms of synaptic drive onto a single pyramidal neuron is an instance of antagonistic regulation which allows gear-shifting of inputs, and in this case, allows very strong inputs to be downshifted by inhibition to a weaker effect on the membrane potential. What is the advantage of such a scheme? Strong signals are less prone to noise and uncertainty than weak signals. Weak signals are filtered out by the inhibitory drive. Strong signals allow unequivocal signal transmission, whether excitatory synaptic input, (or phasic increases of dopamine levels, in other contexts), which are then gear-shifted down by antagonistic reception. There may also be a temporal sequence: a strong signal is followed by a negative signal to restrict its time course and reduce impact. In the case of somatic inhibition following dendritic excitation the fine temporal structure could work together with the antagonistic gear-shifting exactly for this goal. Okun and Lampl, 2008 have actually shown that inhibition follows excitation by several milliseconds.

But what are the implications for an E/I network, such as cortex?

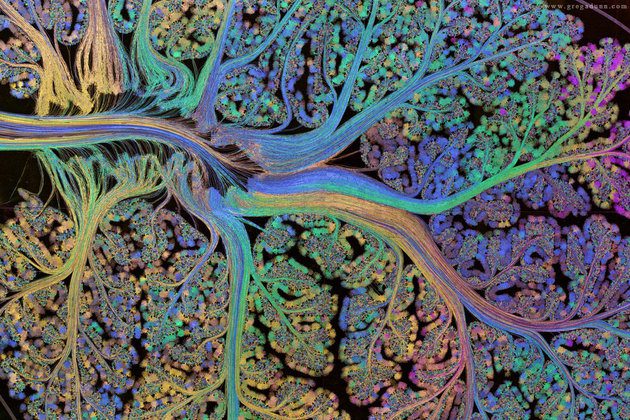

Here is an experimental result:

During both task and delay, mediodorsal thalamic (MD) neurons have 30-50% raised firing rates, fast-spiking (FS) inhibitory cortical neurons have likewise 40-60% raised firing rates, but excitatory (regular-spiking, RS) cortical neurons are unaltered. Thus there is an intervention possible, by external input from MD, probably directly to FS neurons, which does not affect RS neuron rate at all (fig. a and c, SchmittLIetal2017)

Mediodorsal thalamic stimulation raises inhibition, but leaves excitation unchanged.

At the same time, in this experiment, the E-E connectivity is raised (probably by some form of short-term synaptic potentiation), such that E neurons receive more input, which is counteracted by more inhibition. (cf. also Hamilton, L2013). The balance on the level of the single neuron would be kept, but the network exhibits only loose regulation of the I/E ratio: unilateral increase of inhibition.

There are several studies which show that it is possible to raise inhibition and thus enhance cognition, for instance in the mPFC of CNTNAP2 (neurexin, a cell adhesion protein) deficient mice, which have abnormally raised excitation, and altered social behavior (SelimbeyogluAetal2017, cf. Foss-FeigJ2017 for an overview). Also, inhibition is necessary to allow critical period learning – which is hypothesized to be due to a switch from internally generated spontaneous activity to external sensory perception (ToyoizumiT2013) – in line with our suggestion that the gear-shifting effect of locally balanced I/E allows only strong signals to drive excitation and spiking and filters weak, internally generated signals.